Retention of volunteers in the emergency services: exploring interpersonal and group cohesion factors

Simon Rice, Barry Fallon

Peer-reviewed Article

Abstract

Article

Editor's note: Sections of this manuscript were presented at the 8th Industrial & Organisational Psychology Conference of the Australian Psychological Society, June 2009, Sydney, Australia.

Australia’s emergency services sector is heavily reliant on the contribution of trained, experienced and committed volunteers. Of concern, within the last decade, the average time contributed by volunteers to emergency service agencies has decreased and the recruitment of volunteer personnel has become increasingly difficult (Baxter-Tomkins & Wallace, 2006; 2009). One commonsense approach to maintaining volunteer numbers is to minimise attrition through retention practices that seek to provide benefit to volunteers, increase morale, and facilitate commitment to the agency (McLennan & Bertoldi, 2004).

Social exchange and volunteer motivations

Volunteer motivation can be conceptualised within the framework of social exchange theory – in order for volunteer efforts to be sustained over time, the rewards to the volunteer must exceed, or at minimum, balance out the costs (Schafer, 1979). The decision to continue volunteering is typically re-evaluated throughout the volunteer’s tenure, where assessments are made about the relative rewards and costs of their involvement (Philips, 1982).

Research demonstrates that the expansion and mobilisation of personal relationships and social networks is a key benefit perceived by individuals seeking to volunteer within emergency service agencies. Volunteer fire-fighters report being motivated by a range of community safety concerns, community contribution desires, and enlightened self-interest, with those in the 18–34 age range likely to be attracted by personal benefits of volunteering such as career enhancement, skill development, and opportunities for friendship and camaraderie (McLennan & Birch, 2008). Surf lifesavers identify that participation in an organisation with structured training that coexists with a beach lifestyle and contribution to community safety were primary motivators, followed by social factors such as camaraderie, recognition and appreciation from others (Hall & Innes, 2008). Amongst volunteer ambulance officers, community contribution, skill acquisition, achievement and social benefits were reported as important motivators (Fahey, Walker & Lennox, 2003). While emergency service volunteers report high levels of camaraderie and social connection to others as a consequence of involvement, conflict and dysfunction within the workgroup can quickly erode such social benefits, and may prompt volunteers to resign (Baxter-Tomkins & Wallace, 2009). Consistent with this, when volunteer fire-fighters were asked in exit interviews what they least enjoyed about volunteering, the most frequently identified responses related to poor brigade climate characterised by conflicts, factionalism, exclusion, and bullying (McLennan, Birch, Cowlishaw, & Hayes, 2009). Further, McLennan and colleagues reported that 25% of volunteers discontinued their involvement because of disputes with other members, exclusion from brigade activities, concerns regarding the direction of the agency, and losing interest in the role of volunteer.

An additional factor that assists with volunteer retention is recognition and acknowledgement. Despite high levels of service delivery, it has been argued that those working within the emergency services in Australia experience a broad lack of recognition (Howard, 2003). Recognition of volunteers is of particular concern to emergency service agencies given that organisational studies repeatedly find that staff frequently quit in instances where they feel undervalued (e.g. Lilienthal, 2000). Recognition of service is a symbolic gesture that undoubtedly carries importance for emergency service volunteers and agencies must tread the fine line in balancing easily achievable versus unobtainable reward and recognition systems for their volunteers (Aitken, 2000). While many services provide public recognition and award opportunities for their volunteers, dissatisfaction with some programs has been reported on the basis of long periods of time required for award eligibility (McLennan, 2005).

The current study

For emergency service volunteers, the rewards of their involvement will be varied and idiosyncratic, but are likely to draw on the social benefits experienced through camaraderie, expanded social networks, and recognition from the agency or wider community. Within the framework of social exchange theory the present study examined the contribution of interpersonal and group cohesion factors on emergency service volunteer satisfaction and turnover intention. Interpersonal factors, conceptualised to include volunteer perceptions of supervisor support, fairness in the implementation of policies and procedures, and the degree of recognition experienced by the volunteers were all expected to increase satisfaction and ongoing commitment to the agency.

Method

Participants

Data was analysed from 2306 volunteer personnel (246 of which were female), recruited within an Australian state based emergency service provider. The agency comprises approximately 60,000 volunteers and 1,000 paid office administration, technical and management staff. The total response rate represented 4% of the total volunteer population within the agency (see Table 1 for a breakdown of participant age and tenure).

Table 1. Participant Age (top) and Tenure (bottom).

| Age Group | n | % within sample |

|---|---|---|

| 25 years or less | 146 | 6.3 |

| 26 – 35 years | 223 | 9.7 |

| 36 – 45 years | 495 | 21.5 |

| 46 – 55 years | 629 | 27.3 |

| 56+ years | 805 | 34.9 |

| Tenure | n | % within sample |

|---|---|---|

| 2 years or less | 193 | 8.5 |

| 3 – 5 years | 320 | 14.0 |

| 6 – 10 years | 358 | 15.7 |

| 11 – 20 years | 486 | 21.3 |

| 20 – 30 years | 455 | 19.9 |

| 31 – 40 years | 251 | 11.0 |

| 40 + years | 221 | 9.7 |

Procedure

Volunteer members of the emergency service agency were made aware of the research project via a promotional campaign where notices were placed in the agency’s publications, and posters were displayed at local depots and offices. A hardcopy of the survey was distributed as an insert within the agency’s quarterly magazine along with reply paid envelopes. Participants could also complete the questionnaire online. Members were made aware that the survey was anonymous and confidential.

Measures

The current study reports a subset of data collected as part of an organisation wide climate survey. All questionnaire items were presented to participants on seven point scales where 1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree. Sample items for the six scales used within the current study (group cohesion, intention to leave, interactional justice, job satisfaction and recognition) are listed in Table 2. All scales demonstrated satisfactory reliability for the current sample.

Table 2. List of Scales, Reliability Coefficients and Sample Items.

| Scale | Reliability (α) | Sample item |

|---|---|---|

| Group Cohesion (Developed for Current Study) |

.80 | ‘Members at my agency readily take action when others are not being treated with respect’ |

| Intention to Leave (Colarelli, 1984) |

.79 | ‘I frequently think of leaving my agency’ |

| Interactional Justice (Moorman, 1991) |

.93 | ‘Supervisors at my agency treat members with consideration’ |

| Job Satisfaction (Wright & Croponzanno, 2000) |

.91 | ‘I am satisfied with my role’ |

| Recognition (Martin & Bush, 2006) |

.87 | ‘Members can count on a pat on the back from the agency when they perform well’ |

| Supervisor Support (Patterson et al., 2005) |

.95 | ‘Supervisors show an understanding of the members who work for them’ |

Results

Scale means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients are presented in Table 3. All inter-correlations were statistically significant, and ranged from medium to large.

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations, and Inter-correlations among Study Variables.

| Scale | M (SD) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Group Cohesion | 5.02 (1.44) | - | |||||

| 2. Intention to Leave | 1.86 (1.35) | -.37** | - | ||||

| 3. Interactional Justice | 4.69 (1.44) | .64** | -.42** | - | |||

| 4. Job Satisfaction | 5.34 (1.36) | .34** | -.55** | .66** | - | ||

| 5. Recognition | 4.42 (1.53) | .59** | -.36** | .72** | .65** | - | |

| 6. Supervisor Support | 4.69 (1.48) | .68** | -.41** | .79** | .72** | .76** | - |

Note. **denotes significant at p < . 01 (two-tailed).

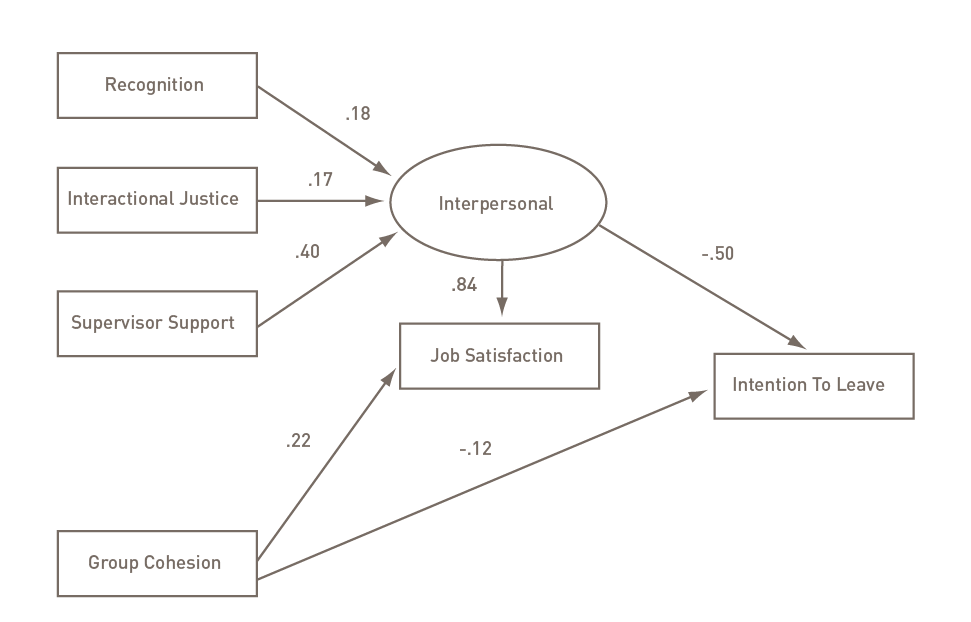

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to explore the relationships between interpersonal factors and group cohesion on satisfaction and intention to leave. The model used in the current study comprised three scales (supervisor support, interactional justice and recognition) contributing to the latent variable named interpersonal factors. This latent variable was then used to predict job satisfaction and intention to leave. In addition, the group cohesion scores were simultaneously regressed upon job satisfaction and intention to leave (see Figure 1). Indices of fit were all excellent1, indicating that the hypothesised model fit the observed data very well.

Figure 1. Standardised beta weights predicting interpersonal variables and group cohesion to job satisfaction and intention to leave.

In summary the model indicates that supervisor support, interactional justice and recognition all significantly contribute to the latent variable, interpersonal factors. For every one unit increase in volunteer’s perceptions of interpersonal factors, there is a corresponding increase of .84 in volunteers perceptions of job satisfaction, and a corresponding decrease of .50 in intention to leave the agency. Further, for each unit increase in group cohesion there is an increase of .22 in job satisfaction, and decrease of .12 in intention to leave.

Discussion

In focusing on the social exchanges that occur through interpersonal and group cohesion factors, the current study identifies aspects of the volunteer experience that enhance satisfaction and ongoing commitment. Consistent with the notion of mobilisation of personal relationships (Baxter-Tomkins & Wallace, 2009) and the impact of team climate (McLennan, Birch, Cowlishaw, & Hayes, 2009), findings indicate that interpersonal and group cohesion factors within the workgroup significantly contribute toward volunteers’ perceptions of satisfaction and future volunteering intentions. This research contributes to the list of studies indicating the essential role played by social factors in determining involvement and retention of emergency service volunteers (e.g. Fahey, Walker & Lennox, 2003; Hall and Innes, 2008; McLennan and Birch, 2008).

The results of the present study fit neatly within the framework of social exchange theory – that volunteers maintain their involvement with the agency when perceived rewards outweigh, or are equal to perceived costs (Philips, 1982). Perceptions of recognition, fairness of procedures, and supervisor support all related to increased satisfaction and future intentions to remain committed to the agency. These domains can be viewed as some of the tacit and symbolic rewards that emergency service volunteers receive – credit and acknowledgement for a job well done, and consideration, interest, support and concern from superiors. Further, similar to the interpersonal factor, group cohesion was also associated with greater volunteer satisfaction and future commitment. This highlights the important role played by agency workgroup climate, whereby volunteers are clearly sensitive to the degree of cohesion within their workgroup unit, which in turn impacts upon feelings of satisfaction with the volunteering role.

Within the model tested, volunteers perceived the relationship with their direct supervisor as the greatest determinant of job satisfaction and future volunteering intention. The quality of local volunteer leadership has been noted as the most critical of all factors in promoting volunteer retention (Aitken, 2000). Being a member of a well led, inclusive and harmonious team is typically associated with higher levels of satisfaction and intended commitment to the agency, and to this end, as indicated by McLennan and colleagues (2009), emergency service agencies should look to strengthen training in leadership and people management skills for supervisors. Although costly, such training will give supervisors skills in managing workgroup culture through leadership and modelling. In addition to promoting retention, this may in turn lead to greater efficiency and responsiveness in the face of emergencies.

The group cohesion factor primarily assessed respect amongst volunteers for one another, and informal intervention amongst volunteers when harassment and discrimination norms are violated within the workgroup. As such, the group cohesion factor assesses the internalisation of prosocial and inclusive practices amongst volunteers. Naturally, when group cohesion is high, the social identity of the unit or brigade is collectively understood and supported by all, leading to a positive interpersonal climate. Group cohesion requires good leadership, and supervisors must be always mindful of the interrelationships within their workgroup, directly intervening when necessary. This requires a degree of skill, further underscoring the need for effective supervisor training schemes.

Also of importance to retention is the degree of reward and recognition experienced by volunteers. Currently, formal awards within the emergency services require arduous long-term volunteer commitment, or demonstration of valour or bravery (McLennan & Bertoldi, 2005). Other forms of recognition should be explored such as agencies sponsoring attendance at professional development activities (e.g. Hagar & Brudney, 2004), offering scholarships and study awards (e.g. Aitken, 2000), or hosting regular informal public acknowledgement ceremonies such as volunteer appreciation luncheons or barbeques. On these occasions volunteers may receive certificates, plaques, or t-shirts honouring their contribution.

Further research may seek to examine the specific factors that generate volunteer commitment to agency. Focus groups may serve to identify the specific recognition needs and wants of subgroups across agencies. Implementation trials could then be undertaken, and tracked in conjunction with exit interview data, or figures provided by HR sections. In addition, future research may seek to assess more specifically the types of social benefits that volunteers receive. For example, studies may seek to explore the organisational impact of regular informal social functions where volunteers can enjoy the company of others and strengthen social bonds. Further, future researchers may also profit from exploring volunteers level of understanding of equal opportunity and diversity practices within their respective agencies. Given that many emergency service agencies are primarily composed of male, English speaking Caucasians (Baxter-Tomkins & Wallace, 2006), future recruitment of members from multicultural backgrounds may significantly boost personnel numbers.

Conclusion

Retention of volunteers is a commonsense way to ensure adequate numbers of trained and experienced personnel are available to attend to emergencies. To enable policy makers to develop successful retention programs, the specific factors that motivate emergency service volunteers need to be identified. By viewing findings in the light of social exchange theory, this study provides a platform for appreciating that volunteers continually reassess and balance the rewards and costs of their involvement. Positive interpersonal relationships with supervisors, recognition, and group cohesion all appear to contribute to greater satisfaction and intention to remain committed to the agency in the longer term. As these are among the few benefits that emergency service volunteers receive, agencies should seek to maximise their impact and presence in the interest of retaining a qualified and experienced volunteer workforce.

Interpersonal and group cohesion factors contribute to volunteer satisfaction.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the emergency service agency from which the study data was collected.

References

Aitken, A. (2000), Identifying key issues affecting the retention of emergency service volunteers. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Vol. 15, pp. 16–23.

Baxter-Tomkins, T., & Wallace, M. (2006), Emergency service volunteers: What do we really know about them? Australian Journal on Volunteering, Vol. 11, pp. 7–12.

Baxter-Tomkins, T., & Wallace, M. (2009), Recruitment and retention of volunteers in emergency services. Australian Journal on Volunteering, Vol. 14, pp. 1–11.

Byrne, B. M. (2001), Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah: New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Colarelli, S. M. (1984), Methods of communication and mediating processes in realistic job previews. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 69, pp. 633–642.

Fahey,C., Walker, J., & Lennox, G. (2003), Flexible, focused training: Keeps volunteers ambulance officers. Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care, Vol. 1, pp. 1–2.

Hall, J. & Innes, P. (2008), The motivation of volunteers: Australian surf lifesavers. Australian Journal of Volunteering, Vol. 13, pp. 17–28.

Hager, M., Brudney, J. (2004), Volunteer management: Practices and retention of volunteers. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute.

Howard, H. (2003), Volunteerism in emergency management in Australia: Direction and development since the national volunteer summit of 2001. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Vol. 18, pp. 31–33.

Lilienthal, S. M. (2000), What do workers really think of your company? And if they leave, what can your firm learn from their departure. Workforce, Vol. 79, pp. 71–76.

Martin, C., & Bush, A. (2006), Psychological climate, empowerment, leadership style and customer oriented selling: An analysis of sales manager-salesperson dyad. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 34, pp. 419–438.

McLennan, J. (2005), Recruiting Australia’s rural fire services volunteers. Present and future challenges. Australian Journal on Volunteering, Vol. 10, pp. 52–55.

McLennan, J., & Bertoldi, M. (2004), Enhancing volunteer recruitment and retention project. Occasional Report Number 2004:2: Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre.

McLennan, J. & Bertoldi, M. (2005), Australia rural fire services’ recognition and service awards for volunteers. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Vol. 20, pp. 17–21.

McLennan, J., & Birch, A. (2008), Why would you do it? Age and motivation to become a fire service volunteer. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Organisation Psychology, Vol. 1, pp. 7–11.

McLennan, J., Birch, A., Cowlishaw, S., & Hayes, P. (2009), Maintaining volunteer fire-fighter numbers: Adding value to the retention coin. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Vol. 24, pp. 40–47.

Moorman, R.H. (1991), Relationship between organisational justice and organisational citizenship behaviours: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 76, pp. 845–855.

Patterson, M., West, M., Shackleton, V., Dawson, J., Lawthom, R., Naitlis, S., Robinson, D., & Wallace, A. (2005), Validating the organisational climate measure: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, Vol. 26, pp. 379–408.

Philips, M. (1982), Motivation and expectation in successful volunteerism. Nonprofit and voluntary quarterly, Vol. 11, pp. 118–125.

Schafer, R. B. (1979), Equity in a relationship between individuals and a fraternal organization. Nonprofit and voluntary quarterly, Vol. 8, pp. 12–20.

Wright, T.A., & Cropanzano, R. (2000), Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 5, pp. 84–94.

About the authors

Simon Rice is a PhD candidate in the School of Psychology at Australian Catholic University. He has been project manager for a number of research projects examining organisational climate and the experience of emergency service volunteers. He may be contacted at simon.rice@acu.edu.au

Barry Fallon is Foundation Chair and Professor of Psychology at Australian Catholic University. He is an Organisational Psychologist with over 30 years academic and consultancy experience and is Academic Editor of the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Organisational Psychology.

Footnote

1 The current study reports model fit indices of GFI = .998, AGFI = .976, TLI = .988, CFI = .998 and RMSEA = .055. Byrne (2001) suggests that GFI, AGFI, TLI, CFI values above .95, and RMSEA values of below .06 are indicative of a well fitting model.