This article presents results from a survey exploring the understanding by emergency services personnel of the specific needs of LGBTI people before, during and after emergencies. The survey is part of a larger project assisting the emergency management sector to develop LGBTI-inclusive practices and is the first study of its kind in Australia. The survey found that participants felt that LGBTI people were at greater risk of discrimination than did other people both during and following an emergency event. Specific areas identified included reduced access to services, lack of recognition of LGBTI couples and relationships, over-reliance on informal LGBTI networks and trust in mainstem emergency services. The survey also identified negative attitudes towards LGBTI people held by respondents. This article argues that developing LGBTI-inclusive emergency services depends on combining research on LGBTI people’s experiences of emergencies with research on emergency management and personnel’s knowledge and attitudes toward LGBTI people and their particular needs.

Introduction

A small but growing body of research documents LGBTI people’s experiences of emergencies and disaster situations (Pincha & Krishna 2008; D’Ooge 2008; Richards 2010; McSherry et al. 2015; Yamashita, Gomez & Dombroski 2017). This research acknowledges significant variations in LGBTI people’s experiences according to geographic location, race, class and other social variables (D’Ooge 2008; Pincha & Krishna 2008; Dominey-Howes, Gorman-Murray & McKinnon 2014; Yamashita, Gomez & Dombroski 2017). However, its major focus is on what is common in people’s experiences and how heteronormative assumptions influence those experiences including access to emergency services (Dominey-Howes et al. 2016; Gorman-Murray, McKinnon & Dominey-Howes 2016). These assumptions maintain an invisibility of LGBTI people, masking their specific needs and reinforcing heterosexist and discriminatory practices. This can increase their social isolation and risk of discrimination during and after events and can impede their access to services and supports (Balgos 2012, Dominey-Howes et al. 2016, Gorman-Murray et al. 2017, Yamashita et al. 2017).

The majority of this growing body of research has focused on LGBTI people as consumers of emergency services and their experiences of disasters (Balgos 2012; Cianfarani 2013; Dominey-Howes, Gorman-Murray & McKinnon 2014, 2018; Gorman-Murray, McKinnon & Dominey-Howes 2014, 2016, McSherry et al. 2015; Gorman-Murray et al. 2017, Gorman-Murray et al. 2018; McKinnon, Gorman-Murray & Dominey-Howes 2016, 2017). While there have been calls for research to understand the attitudes held by emergency personnel related to LGBTI people (Dominey-Howes et al. 2016, Larkin 2019), this literature review shows that, to date, no such research has been undertaken.

This paper presents the results of a project to address this research gap (Parkinson et al. 2018). The project relies on qualitative and quantitative data from emergency services organisations in Victoria. The aim is to assist the emergency management sector develop LGBTI- and diversity-inclusive practices and models of service delivery.

Recommendations are consistent with the findings of a review of the current literature on LGBTI people’s experiences of disaster events that criticised the lack of polices and frameworks incorporating ‘sex and gender minorities’ (Larkin 2019). However, this paper argues that developing an LGBTI-inclusive emergency sector requires research on the attitudes of emergency management and service personnel as well as their knowledge and approaches to LGBTI clients and staff.

Methodology

An expert advisory group was convened consisting of senior emergency management personnel in Victoria, Australian LGBTI disaster researchers, LGBTI community representatives and staff from the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC). The advisory group met 3 times during the project and provided comment and advice on recruitment, survey questions and preliminary findings and draft recommendations.

The project involved 2 Victoria-wide, online surveys: a client survey asking LGBTI people about their experiences of living through a disaster and accessing services, and an industry survey asking emergency services personnel about their knowledge of LGBTI people, the discrimination they face and the capacity of emergency services organisations to meet the specific needs of LGBTI people.1 The quantitative data was collected using Survey Monkey and Excel. Qualitative data provided in responses to open questions or comments was coded into thematic domains and subcategories using NVivo Qualitative Analysis Software.2

Analysis was conducted by at least 2 researchers and discussed by the research team to improve rigour.

Recruitment for survey participants for the industry survey was via DPC email lists. The industry survey was sent to 7 Victorian Government departments, 14 agencies or authorities and 3 non-government organisations. It was also promoted by emergency sector leaders, including the Victorian Emergency Management Commissioner, via their work-related Facebook and Twitter accounts, on ABC 774 (national radio) and in The Australian (a national newspaper). Ethics approval was through Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project Number 0466).

Results

The results were categorised into 3 areas:

- industry survey respondent data

- respondent knowledge of LGBTI people’s experiences of disaster

- how LGBTI-inclusive respondent’s thought emergency services organisations are.

Industry survey respondent data

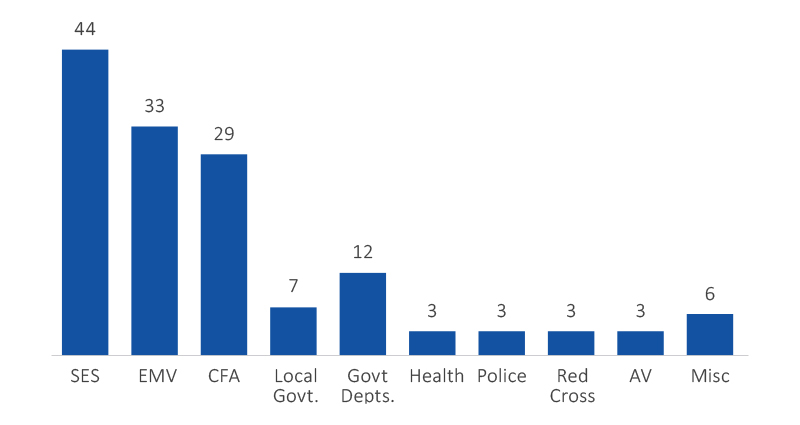

In total, 157 emergency services personnel successfully completed the survey. Of these, 86 identified as male (55%), 63 as female (40%), 6 did not say (4%) and 2 (1%) gave inappropriate responses. Ages ranged between 26 and over 65 years. The majority (94%) of respondents were born in Australia, New Zealand or England and 2% identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people. The survey was targeted to emergency services with a primary responsibility to respond to emergencies. Figure 1 shows the emergency services organisations represented in the survey.

The majority of survey respondents came from the State Emergency Service, Emergency Management Victoria and the Country Fire Authority. Fewer respondents came from government departments, local government, health-related organisations, Victoria Police, Red Cross and Ambulance Victoria. Length of employment at current workplaces varied from one to over 45 years. Sixty per cent were from metropolitan locations, 26% from regional areas and 14% from rural areas. More than half (53%) had front-line emergency roles.

Figure 1: Organisations in which respondents worked (n=143, 14 missing data).

Knowledge of LGBTI people’s experiences in emergencies

Respondents’ attitudes towards LGBTI people were assigned to 4 categories. More than a third (36%) of respondents did not express an attitude towards LGBTI issues and their responses were categorised as unclear. This included respondents who answered only some of the relevant questions. Almost a third (29%) expressed positive attitudes (statements expressing support or willingness to acknowledge LGBTI experiences and needs), 10% expressed negative attitudes (statements against or resistant to acknowledging LGBTI experiences and needs) and 25% expressed neutral attitudes (statements indicating respondents were unaware of emergency issues specific to LGBTI people).

Positive attitudes included comments related to inclusive organisational cultures and, in particular, support for LGBTI inclusion by senior leaders. One response was, ‘Our organisation…would not tolerate any form of homophobic attitudes’. Another was, ‘[H]aving senior leaders from these organisations [a number of key state emergency services organisations] at last year’s pride march was very positive’.

Negative attitudes ranged from hostility to the perception that LGBTI people are ‘special’ and claims that focusing on LGBTI people diverted time and resources from core business. For example, ‘The organisation is too busy dealing with real problems to discriminate against LGTBI individuals’. One response indicated that attention to LGBTI people was at the expense of others:

The only discrimination/comments/remarks I have seen…have been largely against white Australian males and Christians…being inclusive is important but I am seeing Comms and literature at least every week or two about the LGBTIQ community. What about different cultures…the elderly…people with disabilities?

Other responses included overt hostility:

The sooner you lot drop it and stop trying to make yourselves out as victims or different the sooner your perceived problems will disappear. We don't care if you are queer and stop telling us. Get over it.

It was notable that negative attitudes to LGBTI people and issues decreased with age, from 12% of those under 36 years, to 8% of those 56 years and above. Nearly twice as many respondents aged 56 years and above expressed positive attitudes (39%) compared with respondents under 36 years (21%).

Discrimination in service provision

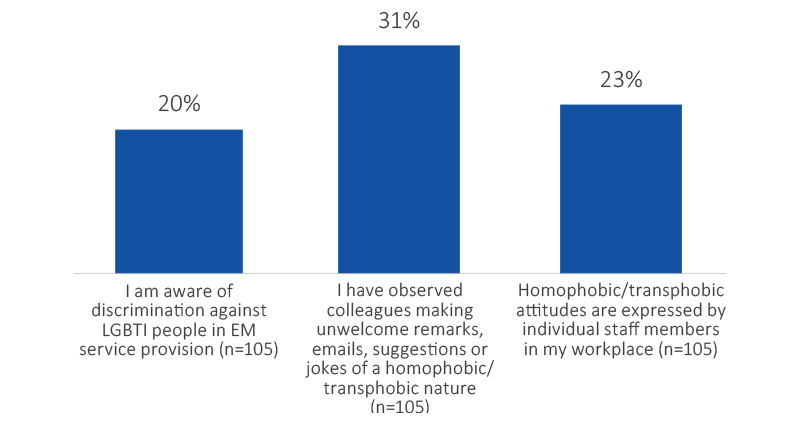

Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement (from ‘not at all’ to ‘the fullest extent’) with 3 statements about discrimination against LGBTI people in emergency services provision. Figure 2 presents the percentage of respondents agreeing with each, aggregating respondents who answered ‘moderate’, ‘great’ or ‘fullest’ extent. Respondents occupied a range of roles and positions, including front-line and office-based workers.

Figure 2: Agreement with statements about discrimination.

One in 5 respondents indicated awareness of discrimination against LGBTI people in emergency services provision. Nearly a third (31%) had observed colleagues making unwelcome remarks, emails or jokes about LGBTI people and 23% indicated that colleagues had shown homophobic or transphobic attitudes. One response was, ‘I know a young man in the CFA who is gay. He pleaded with me not to tell anyone in the brigade, and I haven't’.

Half (49%) of respondents indicated they did not believe that colleagues in other emergency services organisations have a good understanding of the needs or circumstances of LGBTI people in emergencies, while 60% indicated they did not believe that colleagues in their own organisation had a good understanding.

Discrimination in services provision to LGBTI people before, during and after an emergency

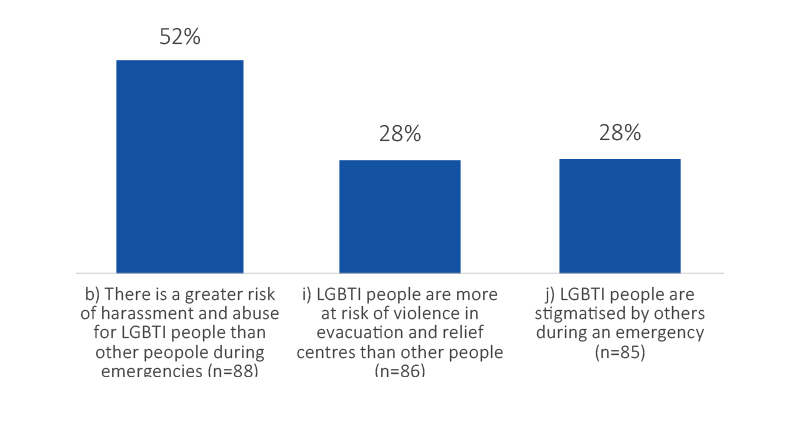

Figures 3 and 4 show responses to 6 statements about perceptions of LGBTI people’s experiences of discrimination and abuse during an emergency. Half (52%) of respondents agreed to the statement that LGBTI people are at greater risk of harassment and abuse during an emergency than others, 28% agreed to the statement that that LGBTI people are at greater risk of violence in evacuation and relief centres and 28% agreed to the statement that LGBTI people are stigmatised during an emergency.

Figure 3: Agreement with statements about LGBTI experiences of discrimination and abuse during an emergency.

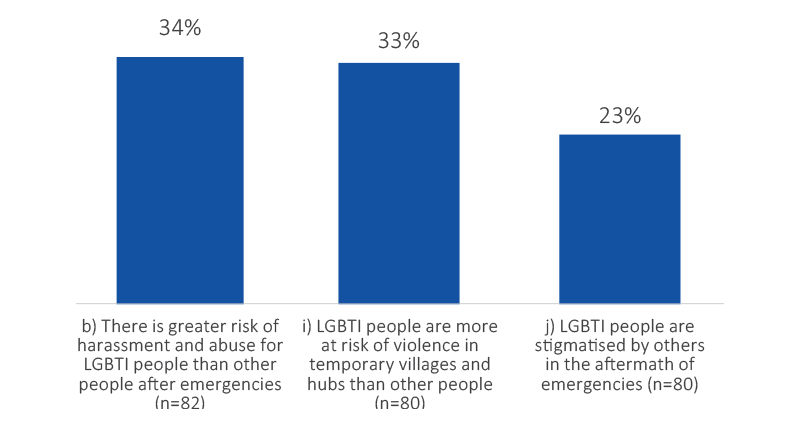

Figure 4: Agreement with statements about LGBTI experiences after an emergency.

One in 3 (34%) agreed with the statement that the risk of harassment and abuse is greater for LGBTI people than for others after an emergency. A third agreed with the statement that LGBTI people are at greater risk of violence in temporary villages and hubs and almost a quarter (23%) agreed with the statement that LGBTI people are stigmatised after emergencies.

Knowledge of LGBTI people’s specific needs in emergencies

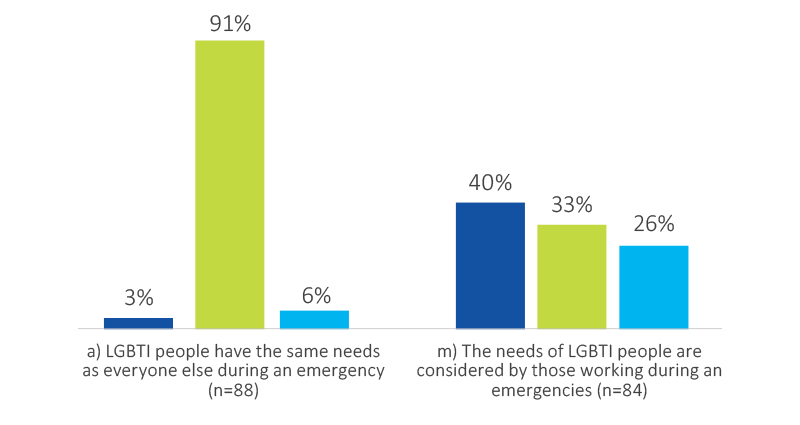

Figure 5 shows respondent agreement with statements about needs during an emergency. Over 90% of respondents indicated that LGBTI people have ‘the same needs’ as others during an emergency. Only 33% indicated that LGBTI people’s needs are considered by workers during an emergency.

While 27 respondents had attended an emergency where individuals had identified as LGBTI, only 6 expressed awareness of ‘emergency’ issues specific to LGBTI people. Nearly a quarter of respondents indicated there are matters particular to LGBTI people that must be addressed in emergency services delivery, for example, family and relationships, help-seeking behaviour, lack of trust, barriers to accessing services and needs of trans and gender-diverse people.

Several respondents did not believe that LGBTI people had any specific emergency needs. For example:

Stop wasting money and time on these bullshit studies because all you are doing is promoting a misconception that LGBTI people are different. [N]ot only is that wrong, but it is the source of the very problem you hypocritically claim to be trying to solve.

Others believed that their particular job did not require an understanding of LGBTI people's emergency needs: ‘not relevant to my job description’.

Nearly a third (31%) of respondents agreed that LGBTI people face more barriers accessing support and resources during an emergency than do other people, and 27% after. Nearly a third (31%) did not agree that the needs of LGBTI couples are considered equally to those of heterosexual and cisgender couples. One in 5 respondents felt it was difficult for LGBTI people to care for their families during an emergency. Over a quarter felt that LGBTI people tend to look after themselves rather than to seek or accept help during an emergency.

A number of respondents raised trust as an issue in the provision of emergency services to LGBTI people. One response was:

[O]ften people who identify as LGBTI have been mistreated or betrayed by individuals or the community in general. Strategies to build trust need to be identified so that the LGBTI community feels it is safe to either seek assistance or information as part of their preparation for or response to an emergency.

Only 16% of respondents agreed there was recognition of the needs of transgender people, including those who may be undergoing gender affirmation.

Figure 5: Agreement with statements about LGBTI needs during emergencies.

LGBTI-inclusive emergency services

Nearly half (47%) of respondents indicated that their organisation did not address the needs of LGBTI people. Half (51%) did not agree that their working environment encouraged LGBTI-appropriate emergency service provision to LGBTI people. One response was, ‘some [LGBTI]…needs are addressed but I don't know if all the needs are even understood, le t alone addressed’.

Three-quarters (74%) of respondents were unaware of organisational policies, procedures or training addressing specific needs of LGBTI people:3

At present our plans do not specifically include action which address LGBTI needs. There is mention of being aware of specific needs of some groups but not targeted at LGBTI individuals.

‘We treat everybody the same’

Some respondents indicated that during an emergency people had similar needs regardless of identity or group affiliation. Good professional practice, they suggested, involved treating everybody the same:

There are no specific policies or procedures, nor should there be. When a person is on fire or trapped in a crumpled car their preferred gender/sexuality is as irrelevant as their skin colour or religion.

Another response was, ‘Just treat all as we would like to be treated or have our loved ones treated’.

The attitude that ‘we treat everyone the same’ was repeated in other comments related to jokes in the workplace:

Jokes and banter involving LGBTI slurs do not constitute Homo/Transphobia as there is no intention to hurt or oppress. Gay jokes should be treated no differently to short jokes, fat jokes, jokes about age. People need to be less precious.

Other responses suggested that casual comments sending up particular groups are free speech and LGBTI people should just get over it, ‘Freedom of speech in this country is what wars were fought for. People need to harden up’.

Developing LGBTI-inclusive emergency services

Reasons for not supporting improvement in services provision to LGBTI people ranged from ‘not required as everybody’s needs are the same’ to ‘Stupid question…Why we have to pedestal these groups is beyond normal comprehension’. Nonetheless, 49 respondents suggested ways emergency services organisations could improve services to LGBTI people. Nearly all indicated that emergency service personnel should be better informed about LGBTI-specific issues. Nearly all responded positively to efforts to reduce discrimination and stigma against LGBTI people in service delivery including organisational leadership and cultural change, developing LGBTI-inclusive policy and procedures and training and professional development.

Responses showed the importance of leadership in organisational change and LGBTI quality service provision:

Where leadership has been supportive, my experience has been positive…where leadership is lacking it’s allowed negative comments.

Responses also highlighted the importance of public support:

Our involvement in the LGBTI parade/march is a positive step to break down negative opinions and open dialogue and our acceptance of diversity.

Policies and procedures

Respondents provided options for including LGBTI people in existing policies and procedures. Responses included a review of charters, policy reminders and statements of management commitment to improve LGBTI-inclusiveness. Others advocated for non-discriminatory recruitment practices reflective of community diversity, assistance with career advancement for LGBTI staff, promotion of LGBTI champions and support for bystander interventions. One response indicated that it was important for staff to call out discriminatory behaviour. Another suggested ways organisational champions can promote higher standards of behaviour and practice:

Ask questions and don't assume; use different pronouns; have examples on posters of diversity; really mean it when you say you support PRIDE march; challenge homophobia at work; have materials available that speak to LGBTIQ people.

Responses included specific recommendations including LGBTI people’s involvement in all stages of developing LGBTI-inclusive policies, procedures and practice; inclusion of options beyond male and female in data collection; attention to LGBTI needs in relief centres and privacy issues for LGBTI people.

Training and professional development

Comments were evenly divided between training and professional development as being essential and those who saw it as an imposition. Those who supported LGBTI-training expressed frustration at the lack of options in the emergency sector, ‘there is no material… that educates the service to the specific needs of this group of people’. Another only became aware of the need for information when a colleague identified as transgender:

I have had supervisory roles with a transgender staff member and to support her I chose to seek out information regarding health and welfare support that may be required while in transition which assisted me greatly. Our policies are more generic.

Some responses indicated that training, including for frontline personnel, would improve the quality of emergency services provision:

Many emergency services are unaware of the different impact of emergencies on women let alone members of the LGBTI community and other minority groups…If emergency services are serious about improving the services for these minority groups, then they would provide appropriate funding [for] awareness training for those at the front-line.

There was also concern that if LGBTI-specific training was not mandated, only staff familiar with the issues and supportive of LGBTI people would attend. An example of the feelings of those opposed to LGBTI-training:

I have not known of these courses taking place, and if they do please don't make it compulsory, my time is too valuable…spend the money on something more important that will benefit all members.

Discussion

This is the first study in Australia to investigate the degree to which the specific needs of sexual and gender-diverse minorities are addressed in the emergency management sector. The study revealed the varied and sometimes contradictory views held by emergency services personnel towards LGBTI people and staff and the development of LGBTI-inclusive practice.

The attitudes of respondents towards LGBTI people during emergencies varied from supportive to open hostility. Nearly 10% of respondents used hostile or discriminatory expressions. This negativity confirms the assertions of LGBTI respondents in other studies (Richards 2010; Dominey-Howes, Gorman-Murray & McKinnon 2014; Parkinson et al. 2021). However, the majority of respondents were either unclear or expressed neutral attitudes towards LGBTI people (61%). At one level, respondent ignorance or indifference to the needs of LGBTI people contributes to and is an effect of heteronormative assumptions that maintain an invisibility of LGBTI people, their relationships and families (see Dominey-Howes, Gorman-Murray & McKinnon 2018 for more discussion). On another level, this is an opportunity to inform personnel about the importance of recognising and addressing the specific needs of the different population groups that make up the community as a whole.

Over a quarter (29%) of respondents expressed positive attitudes toward LGBTI people and a significant minority (25%) felt they have specific needs. Over half (52%) agreed with statements that LGBTI people are at greater risk of harassment and abuse than others during an emergency and over a third (34%) after an emergency. Respondents who indicated that LGBTI people have specific needs in emergencies listed issues including reduced access to emergency services, a lack of recognition of LGBTI relationships, help-seeking behaviours (i.e. relying on informal LGBTI rather than professional networks), lack of trust and pressures unique to transgender people.

A significant minority of respondents indicated concern that LGBTI people and their needs are not acknowledged in organisational policies, procedures and staff training. Some responses showed that while an organisation’s policies, procedures and training included diversity and inclusive practice, and sometimes named marginal groups, LGBTI people were rarely included. This deficit gives tacit support to the attitudes and practices of personnel who believe that LGBTI people have no specific requirements or that good professional practice involves ‘treating everyone the same’. The ideology that ‘we treat everybody the same’ renders LGBTI people and other minority groups invisible. It is also contrary to the terms and recommendations of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (UNDRR 2015). The framework establishes that people and communities are not the same and that emergency services organisations and practices must recognise and respond to the different emergency needs of a diverse population. While there is increasing local and international recognition of the needs of marginal groups in emergency planning, response and recovery, LGBTI people continue to be overlooked, demonstrating how engrained heterosexist privilege and discrimination are.

The findings of this preliminary study demonstrated a lack of awareness of the specific needs of LGBTI people among emergency services personnel. At the same time, there is support from within the emergency services sector for the development of LGBTI-inclusive policies, procedures, practices and training. A detailed list of recommendations arising from this research include actions that governments and emergency services organisations could undertake to bring about culture change (Leonard et al. 2018). This, combined with attention by emergency services organisations, for example by implementing the Gender and Emergency Management Guidelines, could bring culture change. There is a pressing need for more qualitative and quantitative research on emergency services personnel understandings of the needs of LGBTI people and communities in their planning, response and recovery. There is also a need for detailed research on the experiences of LGBTI staff and volunteers (Parkinson et al. 2021). In the Australian context, there is an opportunity for an LGBTI-inclusive audit of government and emergency services organisations disaster and relief policies and planning to establish a baseline against which ongoing improvements in LGBTI inclusion can be measured.

Conclusion

Focusing on LGBTI people’s disaster experiences is vital to ‘queering…research and policy in relation to natural disasters’ (Dominey-Howes et al. 2016). This research makes LGBTI people and their needs visible and challenges the heteronormative assumptions that inform emergency research and policy. However, promoting the development of LGBTI-inclusive emergency services and sector-wide organisational systems and work cultures depends on promoting inclusion of LGBTI issues in disaster research and policy. It also requires research on the attitudes of personnel and the degree to which their organisations address LGBTI people’s needs. Combining these strands can create an emergency management sector where LGBTI people’s needs are addressed in advance as part of diverse, inclusive professional practice. This is a model of service provision where LGBTI people can be confident that their needs and identities are acknowledged, supported and affirmed.